Cusco may have been the Inca Empire’s holy city, but it was also the nexus of their legendary network of thoroughfares, spanning all points in the empire. Just north of Cusco looms the fertile and fabled homeland of the Inca Empire, the Urubamba Valley. More commonly known as the Sacred Valley, this exquisite expanse of undulating countryside and evocative landscapes is steeped in Andean history and culture.

Spanish naturalist, Antonio de Leon’ Pinedo, dubbed the region a Garden of Eden, and it’s hard to disagree. There’s a pervasive sense of awe and saga to the valley, ablaze in shifting light, multi-coloured wildflowers, pisonay trees and stirring vistas of the snow-cloaked jagged peaks of Andean giants like Mt. Veronica, reaching high to the heavens, with an elevation of 5700 metres. If you’re itching to get your hiking boots on, there’s a plethora of Inca trails woven into the countryside, plus a welter of knock-out ancient sites wreathed in vintage Inca mystique and awe-inspiring engineering ingenuity. To maximise my time, World Journeys hooked me up with their outstanding team of on-the-ground local guides at Condor Travel.

My first stop was Moray, a mammoth Inca construction, resembling a colossal multi-level amphitheatre with concentric stone terraces carved out of the deep earthen bowl, leading down to a natural sink hole, providing for great drainage. This triumphant Inca agricultural project, equipped with irrigation, was developed for crop experimentation, as each level featured a slightly different microclimate to the next.

Those crafty Incans were able to determine what microclimate was optimal for specific crops, particularly maize. The sheer size of these stone crop circles is astonishing, with temperatures differing by as much as 15C, from top to bottom. Although the Inca are credited with the bulk of the project, scientists believe that the lower portion was probably developed by the pre-Inca Wari culture.

A short hop from Moray, salt has been obtained by evaporating salty water from a local subterranean stream in Maras, since 1000BC. I was taken on a cliff-clinging drive up the steep hillside of Maras for a killer view over the Salinas salt pans, a sprawling patchwork of pinks, browns and tans, cascading down the valley. The cliff-side view of these 3000 salt pools is sensational, like gazing down into a salt pool abyss, and somewhat reminiscent of the Moroccan dye pots in Fez. Originally constructed by the Incas, these famed terraced salt pans were created by digging shallow pools into the sloping hillside, after diverting the salty spring water into them.

Upon evaporation, the salt crystallised and continues to be harvested by Peruvians dressed in wide-brimmed hats and traditional woven Andean attire. This community owned and operated salt harvesting scheme continues to be a great money-maker for local families, 500 hundred years after it was first developed.

Have you ever wanted to sleep in a condor’s nest? Driving through the Sacred Valley, I did a double-take when I suddenly noticed zip-liners descending down a cliff face, from what appeared to be a hotel. My eyes weren’t deceiving me. Two years ago, the world’s first hanging lodge was opened in the Sacred Valley, suitably called the Skylodge, which is perched 400 metres up a cliff-face.

Accessing this “hanging lodge”, ingeniously built into the mountain side, requires a 400 metre rock climb. The lodge comprises three vertically hanging transparent capsules, with a maximum capacity for 8 people. If this kind of extreme accommodation, literally out of reach for most people, is your bag – you’ll be in seventh heaven. Upon check-out, the descent entails taking 7 zip-line rides back down to ground-level.

For many visitors to the Sacred Valley, the biggest crowd-pleaser, aside from Macchu Pichu, is Ollantaytambo. As the major rail hub for Macchu Pichu travellers, this ancient town attracts hordes of tourists, but the daily invasion hasn’t stifled it’s remarkably traditional ambience. The locals claim they’ve been growing corn here for 3000 years.

Despite the destructive brutality of the Spanish conquest, Ollantaytambo holds the distinction of being continuously inhabited since the 13th century, and that becomes self-evident, the more you wander around its lanes. You’ll see walls, houses and cobblestoned streets, dating from Inca times, and still in use today. You can step inside an Inca-era home and see guinea pigs running around the kitchen floor, before their grisly date with destiny. The town’s babbling streams feed into the Incan-designed irrigation system, which still faithfully works today.

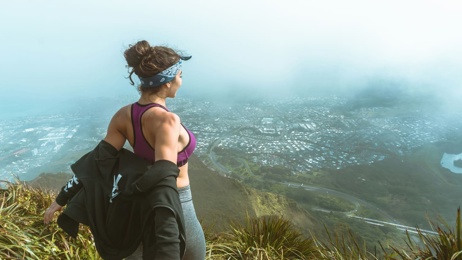

Aside from the exceptional town planning, Ollantaytambo also boasts a blockbuster ancient ruin. The town was formerly a country retreat for Inca royalty and nobility. It’s guarded by a monumental terraced fortress, stacked like pancakes, which leads you up to the ceremonial temple, at the top of the terracing. The complex is still brilliantly intact and you’ll lap up some of the Sacred Valley’s finest panoramas, from the top of the temple. The soaring wrap-around majesty of the granite mountains is what pinch-yourself-moments are made of.

I noticed that some of the exterior walls looked unfinished. My local guide, Jhanet, confirmed my hunch, pointing out that the Spanish conquest abruptly scuppered the project’s completion. All of the granite was quarried from the mountainside 6km away, high above the Urubamaba River. Those ever-inventive Incans carted these massive stone blocks to the water, then diverted the entire river channel, to transport the stone to the fortress site. Yet another can-do marvel of the Inca Empire.

Mike Yardley is Newstalk ZB’s Travel Correspondent on Jack Tame Saturdays. 11.20am.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you