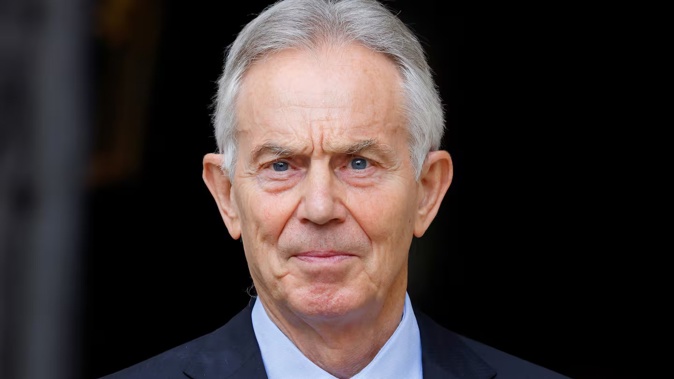

Three decades, five American presidents, and countless burned-out diplomats have come and gone since Tony Blair first took on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as an ambitious, worldly - and supremely self-confident - new British Prime Minister in 1997.

And here he is again.

Blair, 72, has emerged as a key player in planning for the rebuilding and governance of the Gaza Strip if a ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas is finally signed, according to officials in Israel and the United States familiar with the discussions.

A post-war Gaza action plan, significant elements of which were crafted by Blair, a stalwart of centre-left politics, was released today following a lengthy White House meeting between President Donald Trump and Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In a news conference by the two, Netanyahu said he supported it.

Blair’s blueprint is reflected in, among other things, the 20-point plan’s vision of a “new international body” to administer Gaza on a transitional basis.

What it calls a “Board of Peace” would be chaired by Trump, with Blair as a member along with “other members and heads of State to be announced”.

The board would oversee an executive group of Palestinian administrators and technocrats who would be responsible for the day-to-day to running of the Strip and eventually turn governance over to the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority.

The board, according to the plan, is also to be responsible for broad strategic and diplomatic decisions, co-ordinating with Israel and with the Gulf Arab states expected to fund much of the Gaza reconstruction effort, and supervising security through an International Stabilisation Force overseeing local Palestinian police.

Blair’s involvement has caused consternation among many on the Palestinian side, who remember him largely as a co-author of the US-led Iraq War who has consistently sided with Israel in his long career.

His re-emergence at the centre of Middle East manoeuvring is a remarkable next chapter in Blair’s relationship with the region.

He has grappled with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a British PM, a United Nations envoy, a private consultant, and a shadow mediator, refusing to let go of an intractable struggle that has exhausted countless other heads of state and diplomats.

“He has always had a corner of his heart devoted to the unfinished project of calming down this conflict,” former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, who was elected early in Blair’s first term, said in an interview at the weekend. “It’s like he never left.”

Blair’s reappearance within the maelstrom of Gaza negotiations is no surprise to those who have chronicled his career.

Starting with his role in the 1998 Good Friday agreements that ended sectarian violence in Northern Ireland early in his premiership, Blair has embraced the thorniest conflicts, including his rallying of Nato allies for a military intervention in Kosovo a year later.

“There is a strong strand to his personality, this kind of huge confidence that he can solve the most difficult problems in the world,” said British journalist and Blair biographer John Rentoul.

“He will talk to anybody. One of his strengths is that he is pretty unsentimental about working with people that his liberal friends hate, like Trump and Netanyahu.”

Blair has remained well known to all the players in Jerusalem and Ramallah, but not universally beloved.

To supporters (and he has many in Israel), he is a trusted broker who has been seen as potentially helpful in forcing Netanyahu to accept some conditions - such as Palestinian involvement in administering Gaza - that will infuriate Israeli hawks.

“The Israelis cannot easily swallow that idea that the Palestinian Authority will have any part at all,” Barak said. “That could be modified somewhat by having someone like Blair in the middle. They respect him.”

Among Palestinians, however, Blair’s reputation is far more mixed.

Blair did maintain Britain’s traditional position of steadfast support for Israel but calling for a negotiated permanent settlement to the conflict that would see an independent Palestine existing next to a secure Israel.

Palestinian critics say he tilted consistently towards Israel and that his many years of attention to the issue did little to advance the two-state solution he championed.

He declined to do what British Prime Minister Keir Starmer did last week in formally recognising the Palestinian territories as a sovereign state.

For many, the idea of Blair ascending to any sort of governor’s job in Gaza rankles, especially given his role in launching the 2003 invasion of Iraq with US President George W. Bush, based on false reports of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.

Britain’s historic role administering the region under a League of Nations mandate in the years leading up to Israel’s formation doesn’t help either.

“We’ve been under British colonialism already,” said Mustafa Barghouti, general secretary of the Palestinian National Initiative.

“He has a negative reputation here. If you mention Tony Blair, the first thing people mention is the Iraq War.”

A diplomat familiar with Blair’s outreach said Palestinian Authority officials have “engaged” with his proposals. Mahmoud Habbash, a senior adviser to Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, said no one had consulted the body.

“We don’t need another representative,” Habbash said. “The only side that is able to administer Gaza is a Palestinian government and nothing else.”

But in a statement today the Palestinian government said it “welcomes President Donald J. Trump’s sincere and tireless efforts to end the war on Gaza and affirms its confidence in his ability to find a path to peace”.

“Trump has incorporated some of Blair’s thinking into his ... peace plan,” said an Israeli official familiar with the discussions, who like others interviewed for this story spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“It has to be someone acceptable to all sides. The Israelis really like Tony Blair.”

Blair’s personal relations with Netanyahu are also warm, according to people who have seen them together.

“You can always tell when there is tension in the room, and with Blair and Bibi you could tell they got along,” said a one-time member of Blair’s team from his time at the UN Quartet, using a nickname for Netanyahu.

Blair has been promoting many of the ideas since early in the war, which began after Hamas attacked Israeli towns on October 7, 2023.

He is known to have consulted frequently with Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, a key interlocutor with both Netanyahu’s key adviser Ron Dermer and the leaders of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

He’s been rumoured for post-war leadership roles before.

Early in the northern spring, documents distributed by Americans and Israelis drawing up plans for the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation - the US- and Israeli-backed food aid programme that started in May - named Blair as a major figure, potentially even chairman, of an international committee that would oversee and lend credibility to the initiative.

Planners said he and staff from his Tony Blair Institute for Global Change participated in a number of meetings with the group before ultimately backing out of the controversial project.

News reports during the summer also tagged Blair and his institute as participating in what became equally controversial post-war planning that included a proposal to relocate much of Gaza’s population to other countries. The institute later said it had participated only in “listening mode”.

Whatever Blair’s future position will be, along with other key provisions, has yet to be worked out, according to a diplomat in the region familiar with recent discussions.

One of the biggest sticking points remains what role the Palestinian Authority will play in Gaza once Hamas is out of power.

Netanyahu has insisted that the authority play no part, while Abbas has objected to any non-Palestinian governing authority in the enclave.

The new plan explicitly stipulates that no Gazans will be compelled to leave the Strip and that the ultimate goal of a transitional authority is to hand power to a “reformed and strengthened” Palestinian Authority as part, eventually, of an independent Palestinian state.

Blair’s proposals are only one of the blueprints being pushed forward by different parties, including a US$53 billion reconstruction project endorsed by the Arab League.

Trump in February said Palestinians should vacate Gaza while the US came in to rebuild it as the “Riviera of the Middle East”, although he has not repeated the notion recently.

“There are still so many big pieces to work out; anything could still happen,” the diplomat said.

“But there is no question that [Blair’s] ideas have [got] a lot more attention in the last few months. It is what everybody is looking at.”

Blair threw the weight of his premiership into the peace process almost immediately when he took office, lining up behind the ongoing Oslo negotiations and then backing talks between Barak and PLO leader Yasser Arafat brokered by US President Bill Clinton at Camp David.

A few years later, he was credited with nudging a reluctant Bush into proposing the “road map”, a timetable towards Palestinian statehood that went nowhere.

The day Blair left office in 2007, he signed on as the top envoy to the Quartet, a UN-sponsored co-ordinating body made up of the US, Russia, the UN and the European Union.

He also launched his consulting firm and became a senior adviser to JPMorgan Chase at the time, leading to calls that he was mixing diplomacy with business.

Since then, his institute has remained active throughout the region, working for peace, supporters say - or profit, as his critics would have it.

“I thought he would have given up on all this by now,” Rentoul said. “But he hasn’t given up on the idea that he can solve things that no one else can.”

- Karen DeYoung, Miriam Berger contributed to this report.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you