A Nomads member convicted of wearing his gang insignia while at a community event has upped the ante in his challenge of the patch ban legislation.

In his recent fight, Mana-Apiti Brown’s lawyer asked the court to consider how Warriors or All Blacks fans might feel if they were told they couldn’t wear the teams’ supporters’ gear.

Brown, 19, has already unsuccessfully appealed his conviction stemming from last year’s event, at which he was caught on camera wearing a gang cap backwards.

Now, through his lawyer Chris Nicholls, Brown has continued his challenge of the new law by asking the High Court to issue a declaration of inconsistency.

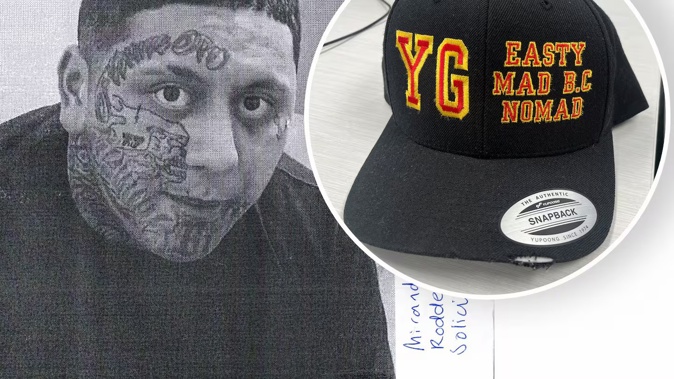

Mana-Apiti Brown of Lower Hutt. Inset of his gang patch cap / Picture supplied.

Brown has claimed the Gangs Act is inconsistent with the Bill of Rights.

If the High Court makes a declaration, and it isn’t appealed, the Attorney-General must notify Parliament. The Minister responsible must then advise the House of the Government’s position on the issue.

But the Attorney-General, represented by Austin Powell and Lauryn Sinclair of Crown Law, has questioned the usefulness of a declaration, stating that when the legislation was passed, politicians were made aware that aspects of the legislation were inconsistent with the Bill of Rights.

Caught on camera

Brown, a patched member of the Bad Company chapter of the Nomads gang, was convicted and discharged in December last year after being seen on CCTV in Naenae wearing a cap with gang insignia on it.

He was in the town centre as part of a community day to celebrate the reopening of the pool, which had been closed for several years while it was earthquake-strengthened.

The Hutt City Council downloaded the footage and reported it to the police, who arrested Brown three days later.

Brown told police the cap, which has the words, “YG Easty Mad B.C Nomad” in red writing with a yellow border, was his uncle’s name in the gang’s writing and colour.

In March, he unsuccessfully appealed his conviction to the High Court after arguing that a conviction for wearing a cap was entirely disproportionate and breached his individual rights.

Now, he’s arguing for his rights of freedom of expression to be recognised so that Parliament might reconsider whether the ban on the display of gang insignia should continue.

At today’s hearing in the High Court at Wellington, Nicholls submitted to Justice Cheryl Gwyn that while his client’s conviction was lawful and proper under the Gangs Act, it was still unlawful because it cut across the fundamental right to freedom of expression under the Bill of Rights Act 1990 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which New Zealand ratified in 1978.

Nicholls told the court that Brown’s actions that day were on the margins of criminal offending, yet he would be tarred with a conviction for the rest of his life.

“My client’s rights have been impinged upon for wearing a cap,” he said, adding that very few would associate the writing with the Nomads gang.

“What 19-year-old doesn’t wear a cap down to the shops? It’s perfectly normal teenage behaviour. Whether they are wearing a rugby league cap, a Bunnings cap, or a Nomads cap, it reflects the age and stage that they are at.”

He said that in wearing the cap, his client was expressing a fundamental human right to express who they are by what they wear.

And he submitted this wasn’t an isolated case, telling the court that around the country, the police were “going hard.”

He cited the case of another client, a Mongrel Mob member, who was sitting in the Pak and Save carpark in Petone, north of Wellington. While moving from the front seat to the back seat of the car, he was caught on CCTV wearing his gang T-shirt.

Police sought a search warrant and not only seized the man’s T-shirt, but also went into his house and searched his washing pile and drawers looking for the shorts and socks he was wearing that day.

Nichollas submitted that there was an obvious disconnect between this activity and the purposes of the Gangs Act, which sought to reduce the ability of gangs to operate and to cause “fear, retaliation, and disruption to the public.”

He said the law cut into an individual’s right of freedom and expression, and when it was passed, Parliament hadn’t fully considered the implications the law would have.

“In a nutshell, it goes too far.”

He asked the judge to consider how Warriors fans would feel if the Government said they couldn’t wear their Warriors jerseys around town anymore, or a law was passed stopping the All Blacks from wearing their black jerseys because the opposition found them too intimidating.

“The gangs are being made out to be different, but when the principal is applied to other groups in the community, the impact of those rights becomes apparent.

“It’s the right to be free, to be human, and to express our rights in the world.

“This law is affecting a large number of New Zealanders probably every day in New Zealand, and hence there is utility in bringing this to Parliament’s attention in addition to the personal remedy my client is seeking.”

The rule of law applies to all

In response, Powell submitted that there would be a lack of utility in making a declaration and that to do so would be inconsistent with the principle of comity.

Powell also submitted that the court would have difficulty in making a declaration of inconsistency in this case, because it would create the impression that a conviction for a law that arguably breached the Bill of Rights was different from a law that didn’t breach it.

“The rule of law applies to all,” he said.

He also submitted that it wasn’t enough to say the law had been passed and was creating problems, so Parliament should look at it again.

That was the function of the Ministry of Justice, not the courts, he said.

Powell urged the court to show restraint and to use its discretion to withhold a declaration of inconsistency in this case.

“The court is saying you passed a law that is inconsistent with the Bill of Rights Act, and what is the utility in doing that when the law was passed knowing that?” he said.

Sinclair also submitted that domestic courts can’t make declarations of inconsistency with the ICCPR.

At the conclusion of the hearing, Justice Gwyn thanked counsel for their submissions, adding that it was an interesting and difficult issue, before indicating she would reserve her decision.

Catherine Hutton is an Open Justice reporter, based in Wellington. She has worked as a journalist for 20 years, including at the Waikato Times and RNZ. Most recently she was working as a media adviser at the Ministry of Justice.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you